In the year 2024, we can comfortably agree that the future of the automotive industry is electric. While headlines have swayed between “electric vehicles are the clear future” and “the electric vehicle market is eternally doomed,” sales have steadily increased year after year, as battery prices fall at similar rates. Whether plug-in hybrid or full electrification, both power trains are much more promising than biofuels or e-fuels. The ease of access to electricity, perceived sustainability benefits by consumers, and outright better driving experience have all resonated with car buyers.

One area with less certainty is how heavy-duty transportation, like trucking, can be electrified. While electrification fits well within the duty cycle of a typical passenger vehicle, the limited charging speed and energy density impact range economics for moving large loads long distances. This uncertainty has attracted the many oil and gas companies looking to hydrogen as a molecule of the future. But can trucking be a real source of hydrogen offtake that project developers target?

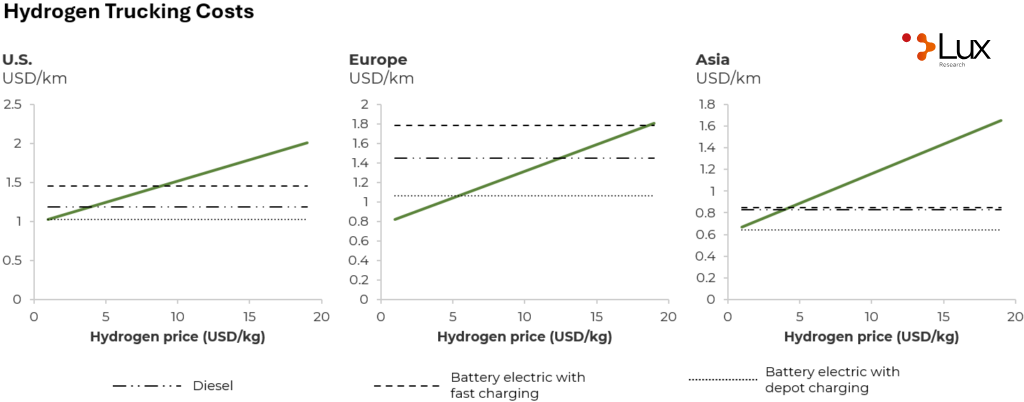

The conversation around what a net-zero future of trucking looks like boils down to two options: a bet on fuel cells, which convert fuels to electricity electrochemically, or direct electrification using batteries to store electricity on-site. To understand which pathway is most likely, Lux Research built an economic model that considers technology and labor costs while factoring in driving regulations that dictate when vehicles can operate and calculated those impacts on costs per mile.

Considering that today’s hydrogen prices range from USD 15/kg to USD 30/kg, using any form of hydrogen essentially makes no economic sense. But as innovations and scale-up of low-carbon hydrogen production lower costs, the key question emerges of just how much cheaper does hydrogen need to get? Is there a feasible pathway to using hydrogen in transportation?

Looking at results in the U.S., a hydrogen price of just USD 4/kg is required to achieve breakeven after 20 years of operation — far longer than most fleet owners want to wait for ROI, and far lower than current hydrogen prices, which hover near USD 30/kg. However the real challenge here isn’t that hydrogen can’t compete with diesel — in reality, regulations will likely drive up the cost of diesel in the future — it’s that the operational costs can’t remotely compete with electricity. The fundamental value proposition of hydrogen as a trucking fuel is predicated on the assumption that batteries won’t be able to support long range nor fast charging. This is a risky assumption; especially given the technical feasibility of concepts like battery swapping, which can be deployed at scale to shorten “charging” times and minimize impacts to the grid.

We consistently hear from our discussions in the energy sector that excitement for low-carbon hydrogen production driven by emissions-reduction goals and generous subsidies can’t replace a fundamental lack of offtake. While there are some ready buyers of hydrogen today looking to replace conventional gray hydrogen with a low-carbon alternative, those looking to sell into the transportation industry won’t see the volumes emerge. The industry’s sensitivity to economics and the high costs of hydrogen fuel make even optimistic projects for hydrogen costs too high to justify support of expanding hydrogen into trucking. Instead, energy clients should seek out existing users of hydrogen while targeting industrial users looking to hydrogen to decarbonize heavy industry as a more receptive and reliable long-term opportunity.