Everything around us has meaning.

Sometimes meaning is very personal to us, like something someone might have done for us at some point in our lives. But most of the time, these meanings are shared in our culture and society. It is these shared meanings that interest us because they teach us about the reasons why we do the things we do and hold the opinions we do.

We all partake in the process of creating and assigning meaning to the world around us. We do this simply through the natural interactions we have with the people around us be it physically or virtually. In the process of trying to make sense of things or take an opportunity to explain something to somebody, we create and assign meaning.

What specifically is meaning?

It refers to the words we use when we are trying to explain or make sense of something in the world around us.

These words we use in the context of something gives meaning to that something.

For example, the way we talk about a topic like “chemicals in skincare products” assigns a set of meanings to the topic. Over time, certain meanings become more dominant while others take on a more repressed position in the context of that topic. What is most interesting perhaps is the fact that in this constellation of meaning, even among the most dominant, a lot of the meanings are quite subtle and implicit. In the sense that if you asked someone, they would find it very difficult to reflect upon their position and talk about those meanings.

Let me give you an example.

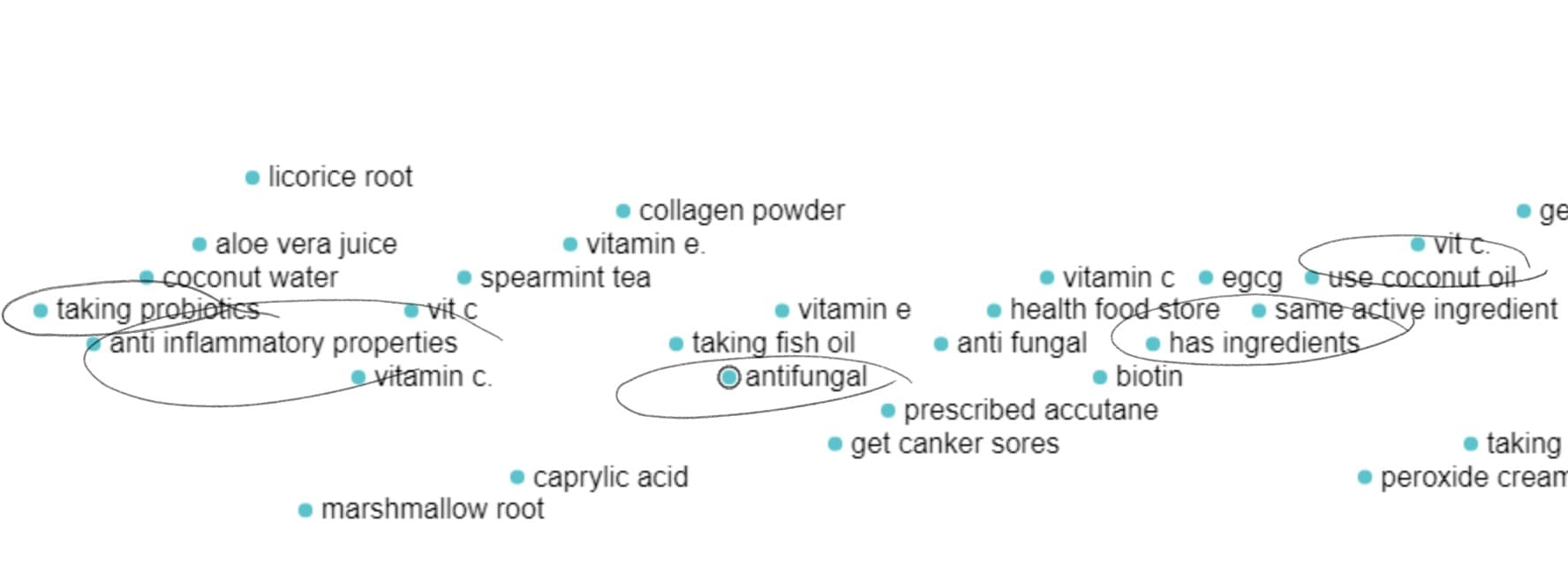

When consumers think about chemicals in skincare, in addition to the obvious – i.e. worrying about the presence of so-called toxic chemicals, they link the issue to an interest in pre- and pro-biotic rich products. In fact, they are so keen on pre- and pro-biotic rich ingredients that they worry about using natural products (as a simple alternative to chemicals) because many have naturally occurring anti-bacterial properties that could harm their skin’s flora.

It will be impossible to get to an insight like this by interviewing consumers. In fact, our client did just that in this case only to discover the expected. Consumers worry about toxic chemicals in products and think they could be either harming their skin in the short term (causing, rather than eliminating blemishes) or worse yet, making themselves susceptible to cancer in the long run. No one discussed the connection between chemicals in skincare and the desire for pre- and probiotic skincare.

That is simply the power of studying meaning in the context of [something].

Consumers just do not make these linkages overtly yet. Examining the broader context of discussions around the topic of “chemicals in skincare” allows us to identify and quantify the dominant meanings – many of which are implicit and often indirectly linked to the culture, yet are in context and therefore give it meaning and shape its future.

Why can’t we just study meaning by asking people the right questions?

The work of the famous philosopher Jacques Derrida teaches us something very relevant and important about decoding meaning.

Human beings, when asked a question, work hard to provide answers that are concise, logically structured, and relevant. This process our brains go through in answering a question is also a process where our brains eliminate a lot of the meanings that are nonetheless shaping our thoughts and opinions, but are difficult to explain or just don’t fit a logical framework with which we need to answer a question. Which is to say that when put on the spot, we all often eliminate meanings rather than articulate and consider them. That is just the limitation of human interaction, one that we can overcome by decoding extremely large samples of data from the natural and organic conversations millions of consumers have on the internet every single day.

By examining the meanings shaping the broader context around a topic, we get to capture all those implicit perceptions and assumptions that consumers make in the normal course of their lives, but that will rarely get communicated in framed discussion.

Studying meaning is a way for us to force ourselves outside the logical paradigm of Q&A. It enables us to see the things that aren’t common knowledge just yet or even fully logical, but are still affecting the future outcomes of our businesses.

Does that mean modern data sciences and analytics engines can better capture meaning?

Yes, but not without an understanding of context. Which is exactly where these engines fail the goal of studying and decoding implicit meaning. Every engine out there studies the “mentions” of a topic. Through “mentions”, they grab data, then analyze patterns in that data-set to report on relationships. This is fine for the purpose of analytics, social media listening, and such tactical exercises.

But it fails in the goal of studying meaning, because more than 70% of the meanings associated with a topic are indirectly established. That is, they rarely exist in the same sentence or “online post” as the mentioned topic.

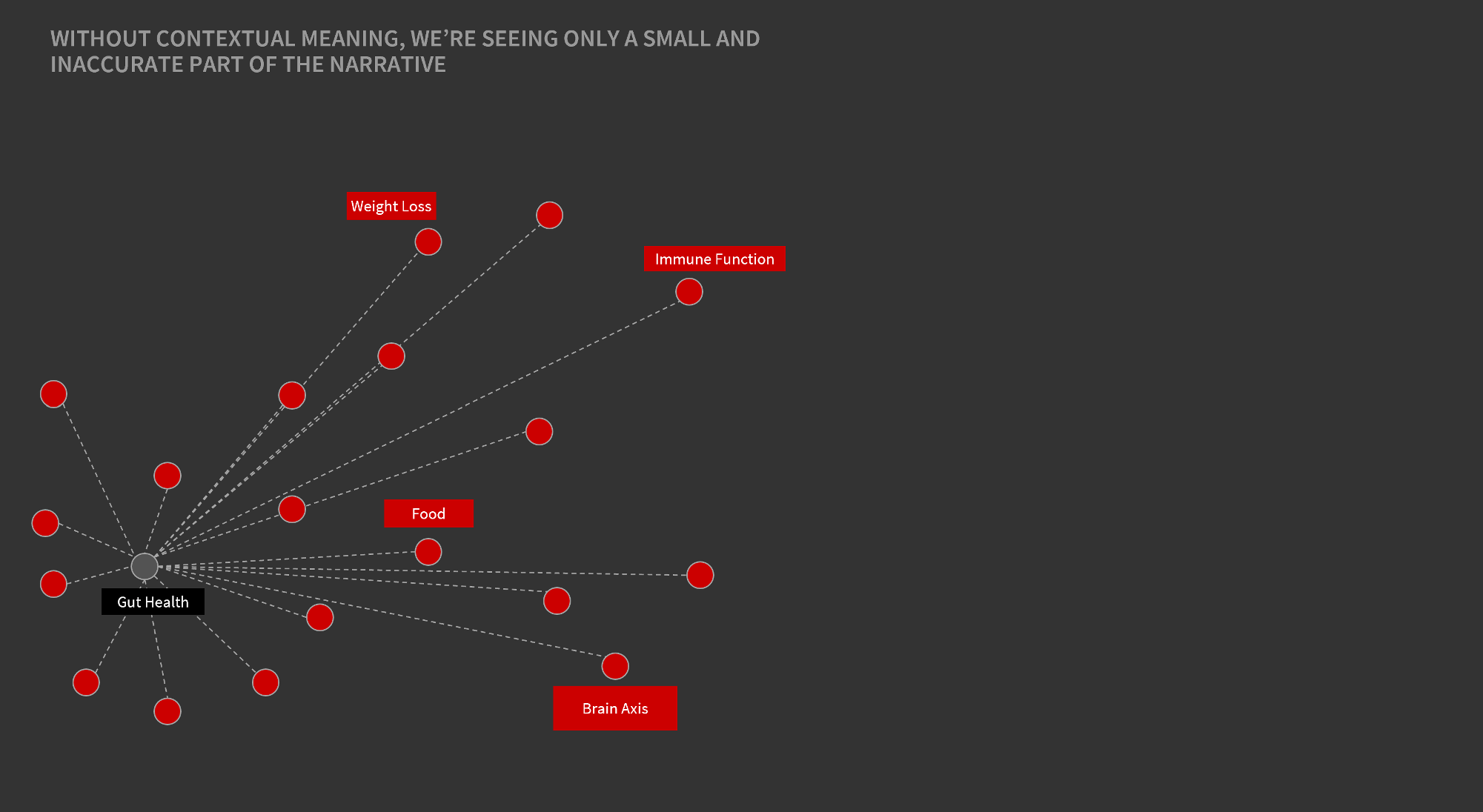

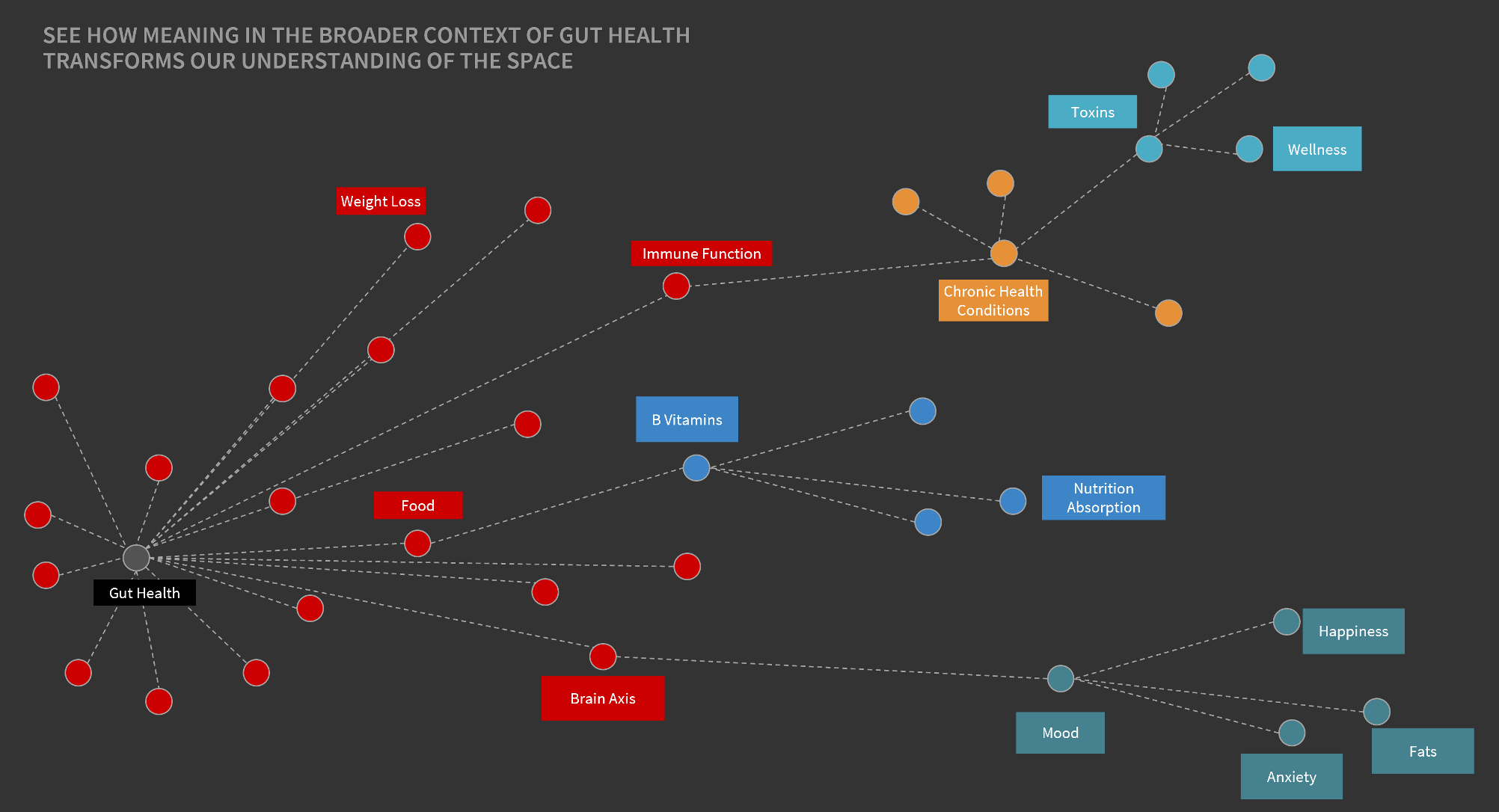

Take the example of “gut health”. If you examine the direct mentions of “gut health” you will see the meanings that are the most explicit or direct. Such as the connection to weight loss or food. The problem is this presents an incomplete picture of what is really going on in this culture.

When you examine the broader context of meanings created around “Gut Health”, you realize that there is so much more going on that was simply hiding in plain sight. It requires contextual intelligence to unearth. In fact, in the macroculture of “Gut Health”, the microculture of “Nutrient Absorption” and “Vitamin Deficiency” is not only one of the most lucrative spaces at the moment, but it is also quietly shaping the future of what makes something legitimate in the context of one’s gut.

If we didn’t have the ability to tap into (and quantify) the meanings shaping the broader context of the culture, we would never have identified any such groundbreaking ideas. Instead, we would have kept surfacing the same insights as everyone else and missed a majority of the forces that are quietly brewing in the backdrop.

That is why the study of meaning requires greater thought and attention to how culture gets created, how it proliferates, grows, or becomes volatile.