The impact of trends on our society, our world, and our businesses is more present than ever before. Every day, new ideas that influence our daily lives lead to more (or less) creative and innovative solutions and directions.

But, what exactly is in the DNA of trends? Where are they born? How are they implemented and when are they over?

What is a trend?

Think of a trend as the beginning of a new direction, taking a turn or a twirl or a twist to something that already exists. It starts something new and then over time, will become more normalized the more it is adopted by the population at large or it will disappear.

What is the origin of a trend?

In order to understand how and why some ideas take hold in culture, and others fade away, we need to first turn our attention to Geoffrey Moore and his concept of “Crossing the Chasm”.

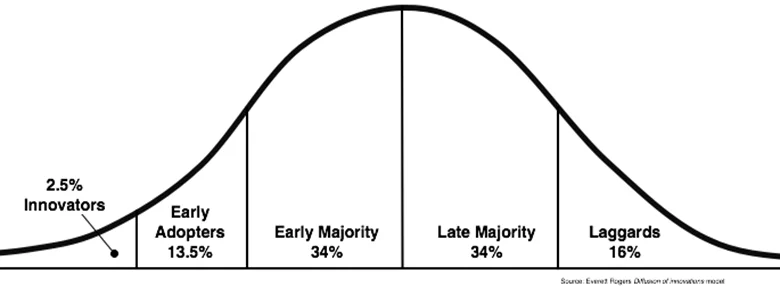

Using the diffusion of innovations theory from Everett Rogers, Moore argues there is a chasm between the early adopters of a product (the enthusiasts and visionaries) and the early majority (the pragmatists).

Moore believes visionaries and pragmatists have very different expectations, and he attempts to explore those differences and suggest techniques to successfully cross the “chasm,” including choosing a target market, understanding the whole

product concept, positioning the product, building a marketing strategy, and choosing the most appropriate distribution channel and pricing.

According to Moore, the marketer should focus on one group of customers at a time, using each group as a base for marketing to the next group. The most difficult step is making the transition between visionaries (early adopters) and pragmatists (early majority). This is the chasm that he refers to.

If you can create a bandwagon effect in which enough momentum builds, then the product becomes a de facto standard, by creating a complete solution for one intractable problem in one business vertical before building out services in adjacent verticals and expanding on from there.

In other words, a chasm denotes a moment in the lifecycle of a market that dictates whether an idea will go on to capture the hearts and minds of the mainstream consumer.

The Chasm tells us that any new idea needs to possess a set of qualities without which it will continue only to resonate with a niche audience or niche market. In many ways, the chasm functions as a gatekeeper, deciding whether an idea is going breakthrough or be forgotten.

But what propels some ideas or trends over the chasm? Is there something that makes trends more likely to make it to the mainstream?

Why do only some ideas turn into mainstream movements?

To answer this question, we turn to the field of Anthropology which teaches us that markets naturally organize themselves1 based on beliefs and conceptually fit quite well into the diffusion of innovation model. Meaning that the beliefs that sit on the fringes clearly make up small percentages of the population while the beliefs held in the mainstream are shared amongst a larger populace.

When an ideology, held by a small group of people is turned into a simple vulnerability or fear, it becomes highly relevant and relatable to a very large group of people. In this process, a trend goes from being niche and about an ideology of some kind to mainstream and becoming about an innately human vulnerability.

Carrying an idea from ideology to vulnerability.

Only those ideas that are able to make the transition from ideology to vulnerability turn into mass/mainstream movements while others just wither away. For ideas to become trends, they need to “cross the chasm”. And to do so, they need a carrier. Typically, this comes in the form of an archetype of consumer or community of consumers that has the uncanny knack of serving as a bridge – they can communicate with different belief sets and have the ability to learn new behaviors from the ideological groups and solve human problems that others (the mainstream) can easily relate to.

Take the idea of coffee in the United States. Coffee used to be a simple a “cup of joe”.

But at some point, a small group of consumers became very concerned about how coffee farmers were being treated specially in the developing world. As a result, fair trade coffee beans became “a thing”.

But this didn’t resonate with the general population. It took a group of consumers to attach a vulnerability to it, to change culture.

What was the vulnerability?

The fair-trade movement which began as an ideology around coffee taught groups of consumers (visionaries from Moore’s model detailed above) that different beans came from different regions and offered intricate tasting notes and sensory profiles. Coffee didn’t just have to be coffee. It could be more complex and treated in the same way one might talk about different types of wine.

Suddenly, these visionaries started to use different types of coffee to exert social status and reinforce their advanced palette. They turned coffee and in particular fair-trade coffee into a form of symbolic capital that exerts status and prestige over others.

The pragmatists, holding their mainstream (traditional) coffee cups suddenly found themselves holding something inferior.

This is what changed the culture of coffee in America.

What creates tension within a culture?

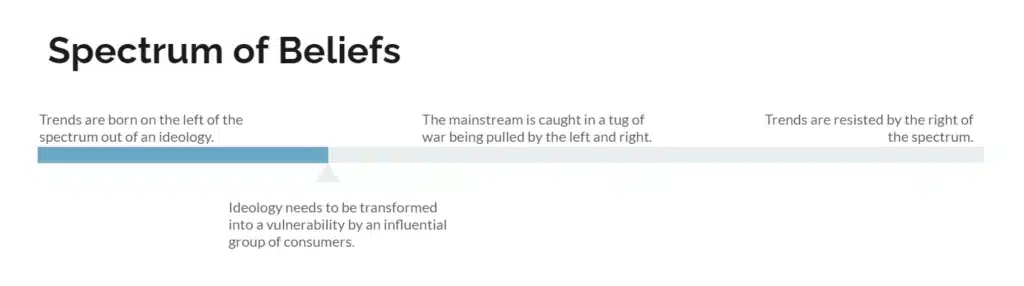

When we think about the evolution of a trend, we need to imagine a political spectrum, with a left, a right, and mainstream consumers stuck in the middle.

Trends are born on the left of the spectrum and, if they cross the chasm as outlined above, they exert pressure on the mainstream to be adopted and implemented among the broader population.

Of course, there is always a right of the spectrum that challenges new concepts, habits, or trends, and exerts pressure to maintain the status quo. In many ways, the left and the right of the spectrum sit at opposite corners of an ideology.

This cultural tug of war is what impacts how quickly or slowly a trend takes hold, and whether it sustains itself or is replaced by a new idea or concept.

Or, in layman’s terms, the more tension there is in a culture, the more ideas are surfacing and battling for superiority, and the more trends are being tested and tabled by consumers. When there is less tension in a culture, that is, less pressure exerted by the left of the belief spectrum to create new solutions and similarly less pressure by the right to maintain the status quo, there is less need for new ideas and less change being demanded by consumers.

In the modern hyper-connected world, a high degree of tension does not just allow new ideas to surface within a culture (or country) but also allows those ideas to dissipate into other cultures, especially those that lack the same degree of intensity in tension. This is why the spread of trends globally is very much culture and context-dependent.

Why trends in certain categories are being driven by certain countries

When we take all the above into account and apply it to trends in a particular category like apparel/style, we start to understand why certain cultures (or countries) are driving more global trends than others. Namely, some countries and their cultures feature more tension, and have more active visionaries promoting new ideas and concepts, whereas, some countries are rather traditional or quite simple in their approach to apparel, and therefore are not currently driving as much innovation or new approaches as others.

This is not to say that trends can not emerge from more traditional markets. It’s just that markets that feature more cultural tension are more prone to have ideological groups who are promoting change, and visionaries who will simplify these ideologies into mainstream trends.

For example, countries like India are currently less polarized when we examine the culture and meaning of apparel and style in the country. The relationship the consumer has with apparel is quite established and comfortable, pun intended. (We see a similar parallel in Spain to a certain extent as well).

Instead, countries like France, the United States, and even China where the meaning of apparel is drastically different across the spectrum carry a significant amount of turmoil and tension and as a result, tend to drive the development of new ideas and trends in the space. Consider this example: In the United States, the culture of apparel exhibits a tension between being seen as successful or well-put together and being vain enough to want to be seen as such. That is, there’s a big push to be comfortable in one’s own skin, yet the pressure of society gets in the way of being able to truly do so and live an “authentic life”. This is why you see designer brands selling ripped shirts and jeans for hundreds (even thousands) of dollars and turning them into a statement for those who sit right in the middle of this tug-of-war and of course, have the means to express themselves in this manner. This scene from the movie “Always Be My Maybe” hits at exactly this tension in a fantastic and hilarious way.

Again, the reason these trends may originate from the US is that there’s significant tension between the ends of the spectrum and as a result, it makes room for new ideas and new innovations to take form and take flight.

Simply put, tension in a culture creates sparks.

The more sparks, the more likely a fire will emerge, and thus, that is where new trends ignite.