Timing is everything in life and in business. You could have the most interesting and valuable idea but if you get the timing wrong the business results will not follow. Historically, insights organizations have relied on a combination of category sales data, trend reports, new launches and investment data to time a new initiative. The problem is, while these data sources give us a great indication of the shifts in the industry, they do not tell us anything about the human side of the story. Which is where the role of anthropology becomes critical.

The field of Anthropology teaches us that new trends cannot come to fruition without the existence of cultural tension.

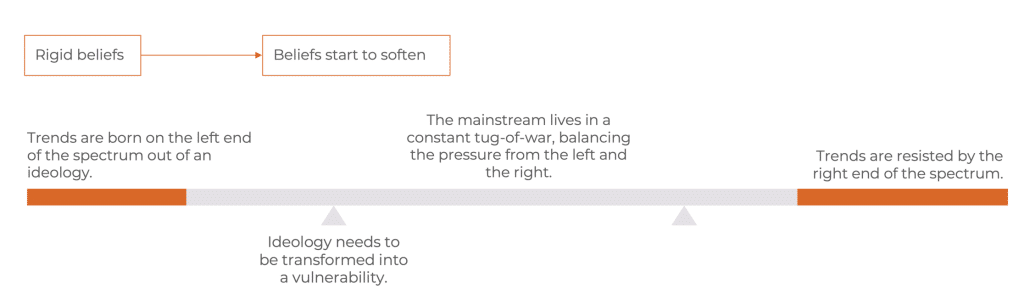

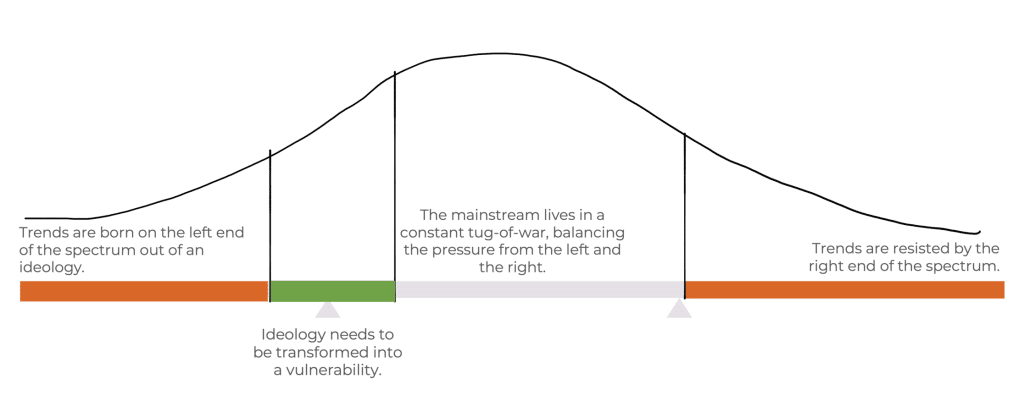

In fact, a deeper examination of how trends come to be will reveal that almost every trend is born on the left-end of a theoretical spectrum where the people creating this new idea tend to have a fairly rigid set of beliefs, and tend to be driven by some kind of ideological mindset. Which of course sits in direct opposition with the established beliefs in that culture on the right-end of the spectrum.

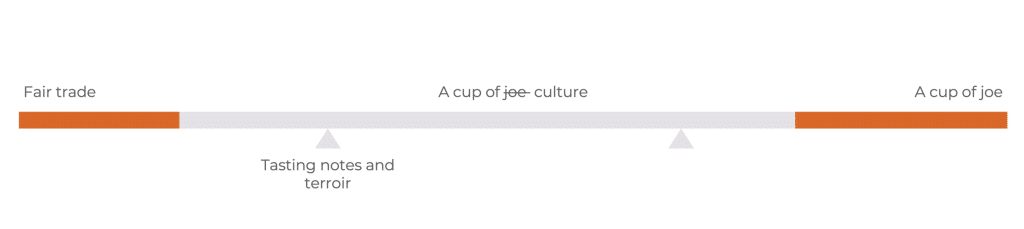

If you put this into the context of modern coffee culture, it’s origin story would begin on the left end of the spectrum, where a smaller ideologically driven group of consumers would express concern over farming practices and the unfair treatment of coffee farmers and farming communities around the world.

Ideologies seldom make their way into the mainstream, which means that these rigidly held beliefs on the left end of the spectrum would have to soften over time for them to eventually gain acceptance from the mainstream. This transformation often happens when the ideology turns into a vulnerability. That is, it turns into a new form of social currency (symbolic capital in bourdieusean terms) that now creates pressure for a slightly larger cohort of consumers to adopt these new solutions and practices in order to stay up-to-date or relevant in their social circles and communities of interest.

In the example of coffee culture, we find that a focus on fair trade, gradually turns into a focus on tasting notes and terroir. New types of consumers flock to the culture of coffee, but this time, instead of focussing on the ideological underpinnings of fair trade, they focus on the experience of drinking coffee that now transports them to a different part of the world, and gives them a wine-esque experience with complex tasting notes and beverage combinations.

As these beliefs continue to soften, they eventually create a new set of cultural requirements for the mainstream, who can now no longer be satisfied with just a Cup of Joe. They too must enjoy elevated coffee, perhaps not with the extent of appreciation as their predecessors, but certainly enough that they don’t look completely ignorant in front of them. And therein is born our modern coffee culture, at least in North America.

Now that we understand how trends proliferate in our culture, let us talk about the role of ‘timing’.

Historically, business and even academic literature teaches us that timing a market is all about getting it done at just the right time. It carries the assumption that there is a single point in time when it is the most optimal to launch a new solution. Which is just not true.

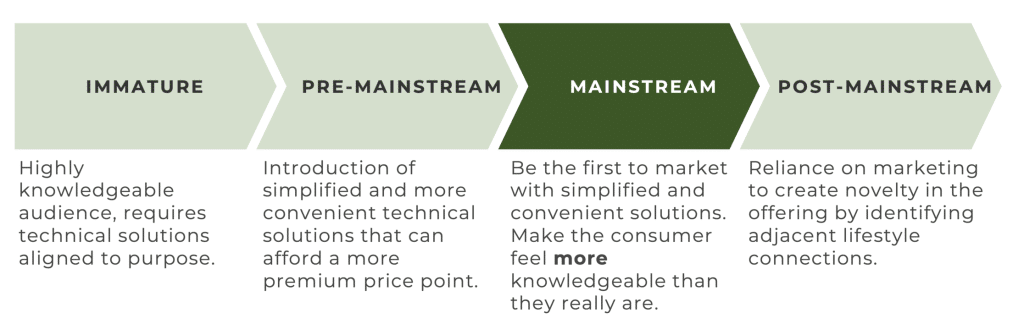

There are, in fact, multiple ways in which one can “time” a market. But of course, depending on the stage of maturity a market/culture is in, the path to success changes along with the cultural requirements one might need to meet. For example, if you were to enter a market while it is still in its immature state – i.e. very much led by an ideology, the pathway to success would require you to be deeply aligned with the intended audience on ‘purpose’. You would need to align on ideologies and engage with a consumer that is highly knowledgeable and perhaps even highly demanding.

In the pre-mainstream stage, when the beliefs of the consumer begin to soften and the culture starts to attract a slightly wider audience base, you no longer require purpose-driven alignment. Instead, you are required to deliver premium solutions that are still technically competent but are a bit more accessible and convenient.

[I was recently in Paris and visited one of my favorite coffee shops called Terres de Café. When I walked in, they were doing tastings with a few customers and also using it as a means to train a new barista. I spent €6 on my first cup of coffee there, a concept that is completely unheard of in mainstream French culture.]

When a culture hits the mainstream, the requirements change once again, as the consumer’s beliefs continue to soften. At this stage, the consumer needs our help, the most. They need our solution to make them feel more knowledgeable (than they are) and are drawn to simplified solutions that are novel or even first to market. Is the market size much larger at this stage? Yes, it sure is. But that does not mean that this is the only stage when one should launch something new. It just depends on what it is that you’re looking to accomplish and why.

Consider this example.

Let’s say I’m trying to disrupt the health supplement market by arguing that it is in fact better (more efficacious) to consume a multivitamin supplement in freeze-dried form than in pill form. Not only am I focused on a technical difference, I am also required to change an already established idea of what a supplement is and how it should be consumed. In such a circumstance, I have no choice but to find opportunities that are pre-mainstream. Because I need to be able to engage an audience that is technically more knowledgeable than the average consumer, and will value my product even more at a higher or premium price point.

On the other hand, if my goal is to bring gut health benefits to the mass market through an existing snacks line, I might take a much different approach looking for opportunities that are in mainstream acceptance already, where the goal of a new solution (an added ingredient to an existing snack for example) is to help people feel more informed and knowledgeable about their snack choices without inconveniencing them.

The post-mainstream stage is no different in this regard, once again requiring a slightly different set of tactics to benefit an organization looking to build market share in an already crowded or saturated cultural space. Here, it’s less about the product and more about how it is marketed and connected into new and adjacent lifestyles. Think of how Mars Wrigley reinvigorated chewing gum by identifying adjacent spaces in gaming culture. A great example of identifying opportunity in a market that is past the mainstream, using the right tactics to effectively time the market with partnerships and tie-ins that drive the required business outcomes.

Timing has two extra dimensions.

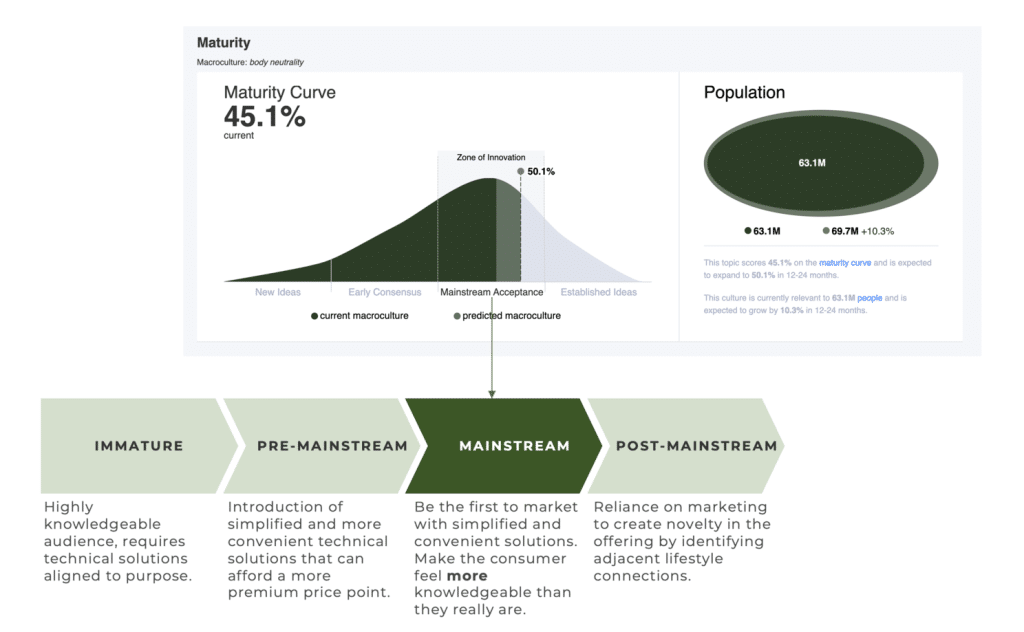

In the example below, the culture/trend of ‘body neutrality’ already sits in mainstream acceptance, which means anything you choose to launch at this stage must meet the particular requirements of that maturity stage, otherwise it will fail to have the impact you desire for the business.

The timing equation is actually rather simple. Mastering timing is really about mastering its relationship to two dependencies because the stage of maturity that a trend or culture sits in shapes what you can do with your solutions and offerings and impacts the pathway (how) you can take to bring it to life. But there is no such thing as the ‘perfect’ time to launch something. It’s time we put that notion to bed.